I always thought there was something fundamentally broken or unfair about people needing to “moonlight” by taking a second job outside their vocation. I had consumed a steady diet of TV police dramas featuring daytime cops with evening jobs as bouncers, security detail, bodyguards, driver safety instructors. Then I began to notice teachers working extra jobs, too. Last year, one of my colleagues supplemented her full time teacher pay working as a waitress at a local restaurant. When did she see her family?

The job of teacher is demanding enough, consuming all one’s time and energy, without the added stress of more time and work. It would feel more whole, be more just, if our teachers could just remain dedicated to their professional art and craft and have time for family, friends, and community; for rest and remaining current in their fields. How do I remain true to my calling while earning enough to survive, now, and retire, later?

Other professions, too, require clean hands: a similar investment of time, service, and diplomacy that appears both impartial and above reproach. The teacher’s craft compares with the doctor’s, clergy’s, governor’s. Many of us cheer the idea of a politician whose hands are not sullied by an inordinate desire for money, and who can practice the wonderful work of statecraft without becoming dependent on the money offered by the pharmaceutical industry or gun lobby. I am thinking that there are noble ideals in teaching; but in acknowledging them I must be wary not to judge myself against an unrealistic ideal. Where do my ideals come from?

The movies

If we applaud the home-y philosopher-stateswoman who is not beholden to special interests, we are not necessarily alienated by the Western-genre myth of a person hired to “clean up the town”. See our mythic heroes John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart. A higher ideal guides such characters, now seen as archetypal, who have come to be embodied in John Ford and Frank Capra movies.

Sometimes these characters step into volatile situations, act to temporarily bring about equilibrium, and leave the town stronger, cleaner, and more whole than when they arrived. All of us humans are touched by some evil or threat of harm, and even if we temporarily gun it down or fight it off, it will outlive us because only something like a love altogether more powerful will disable it. Hints of such better futures are also found in ideal film performances by Clark Gable or Humphrey Bogart. But they are perpetuated in new and original films such as The Post and The Shape of Water in performancesby Meryl Streep and Sally Hawkins.

Both Casablanca and Gone with the Wind end with lovers parting, and someone walking off into a mist, the words “beginning of a beautiful friendship” and “tomorrow is another day” reverberate in the theater as the score swells and the camera zooms out. But we overlook the romanticized heroism or love that redeems such flawed people. Rhet and Rick are profiteers with “hearts of gold”, but they admire idealism in others. Rick sees Ilsa’s and Rhet sees Scarlett’s. Louis is a Nazi sympathizer by convenience; Rhet will fight on the side of the South if it pays better. Everyone is caught between the real world, with its demand for practical tasks, time, and money; and the ideal world, with its tough and courageous love that sacrifices all for family, love, and justice. And most of us, rather than being in love with a single task-specific aspect of our teaching jobs, such as grading papers or taking attendance, are aligned to a more general, abstract habit, such a coaching learners toward independence or encouraging creativity in others.

vocation

That is why I feel the vocation of teaching is caught at this moment in history, caught, like night club owner Rick in Casablanca, between the practical responsibility of running his business (casino, black market) and the romantic heroism of aiding the helpless. In an early scene establishing his virtue and higher calling, he protects a married woman from having to compromise her marriage at the hands of a ruthless, predatory male (who can give her safe passage out of Casablanca in exchange for sexual favors) by fixing the roulette game to ensure her husband wins, then sending them away on an alternate route to safety.

In traditional and archetypal film style, the heroic male is costumed in white and lit strongly; in this shot, I see how Hungarian-born immigrant director Michael Curtiz focuses on the woman’s idolizing gaze at Bogie (Rick), as he, a knight in shining armor, defends her; and while the real love of her life, the man in the foreground, entrusts his savings to Rick. The romantic triangle in tableau foreshadows the actual one eventually played out when Ilsa bargains for her own husband’s safe passage, in order to continue fighting against the Nazis and leading his countrymen to freedom through resistance.

I like hopeful endings: they satisfy my acknowledged preference for justice and honor. I fear that, with many other people today, I also share an unacknowledged preference for the unreal Western myth to be realized in the midst of our daily real lives.

Thus it comes about that we have an national dicussion on the table about whether I, a classroom teacher, should be armed with a pistol in order to protect and defend my students.

The film buff in me has always wanted to be Clint Eastwood, John Wayne, Clark Gable, and Humphrey Bogart — with a little Hercule Poirot and Fred Astaire thrown in.

Do ya feel lucky? Well, do ya, PUNK?

But I sense there is a collision of worlds in this scenario I have not acknowledged. It is a clash between the Platonic ideal of Teacher and the practical reality of Bodyguard. Yet some idealism about my work remains implanted in me. I am hopeful that my vocation and my workplace can retain their integrity of purpose. Learning happens in an environment that is safe, peaceful, and fun; when Jimmy Stewart as Mr. Smith makes his stand in Congress against corruption, he uses his proper tool, his voice, until it wears out; when Eastwood as Dirty Harry patrols the streets of San Francisco to stop a deranged serial killer, he carries the appropriate tool of his trade, a handgun. Movie teachers, in their fictional worlds, carry their spectacles, their Browning versions, their chalk, and their occasional cane or ruler.

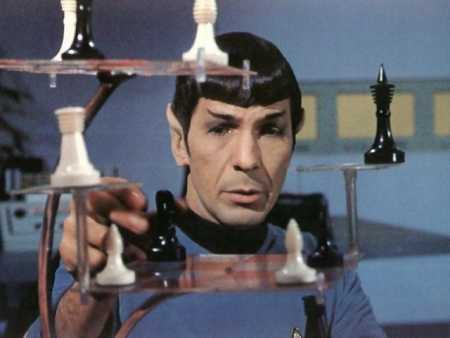

Just what America needs in the classroom: one more phallic symbol of authority and force. I remember a much earlier national conversation steered by the Western myth. We considered the “Star Wars defense system” proposed by Hollywood actor-turned-President Ronald Reagan. To most of my friends, such a mistaken idea was a collision between two worlds: one fictional, in which war was glamorized because it symbolized noble human deeds and ideas (Jedi Knights and The Force) pitted against monstrous cruelty and power (Darth Vader and the Death Star); the other nonfiction, in which human beings on either side might bleed and die, and no one could say with certainty which were the monsters and who the humans.

Just what America needs in the classroom: one more phallic symbol of authority and force. I remember a much earlier national conversation steered by the Western myth. We considered the “Star Wars defense system” proposed by Hollywood actor-turned-President Ronald Reagan. To most of my friends, such a mistaken idea was a collision between two worlds: one fictional, in which war was glamorized because it symbolized noble human deeds and ideas (Jedi Knights and The Force) pitted against monstrous cruelty and power (Darth Vader and the Death Star); the other nonfiction, in which human beings on either side might bleed and die, and no one could say with certainty which were the monsters and who the humans.

Fortunately, there are women to compete with this myth of masculine power. Katharine Graham, whose strength towers over the men in her Washington, D.C. world, those attempting to exert force over her publishing The Pentagon Papers in The Post, resists their influence in order to make her independent choices.

As another Academy Award ceremony is telecast, viewers have a choice of new myths in which to believe. The stories themselves may not be new, since they include historical accounts of such events as The Battle of Dunkirk and the fight to publish The Pentagon Papers. Yet the expression of such stories is meaningful and original.

We witness Katharine Graham make a choice that exposes years of top level government officials’ knowledge about the unwinnability of the Viet Nam war; and in The Shape of Water we feel a tyrant’s monstrous contempt for life, beauty, and weakness countered by a mute cleaning-woman’s love and respect for a captive and complex being. Filmmakers, actors, and writers are only a few of the craftspersons serving as today’s “shapers”, the scops [singer-poets] John Gardner wrote about in his 1971 novel Grendel, a reshaping of the Beowulf epic from the creature’s point of view.

empowered teachers

The decisive Moments in our lives are born in the moments we feel the most powerless. We still need heroes, underdogs, and champions; but we must choose them more carefully today.

On Friday I saw a refreshing film hero with an ancient weapon.

I enjoy knowing that the students next to me during the screening admired this teenage girl’s tenacity; two weeks earlier, I had noticed a couple of others picking out the perfect airsoft assault rifle from an online catalog.

Clearly, we are not the first generation to critique the Hollywood commercialization of the myth of the Old West – its glamor, its icons, its hostility to indigenous peoples and disempowerment of women. Unlike some, though, I don’t feel the need to remove all traces of a trigger-happy culture or of a past for which anyone with privilege used it without a second thought. Warhol alters an iconic image so that we can never see it again as we did before. As summer scholars in El Paso at the recent NEH-sponsored “Tales from the Chihuahuan Desert: Borderland Narratives”, we secondary teachers and UTEP program directors Joseph Rodríguez and Ignacio Martinez saw value in keeping old monuments standing alongside newly erected ones, in order that the whole story could be told and no voices silenced. This new figure of a Tiguan woman stands not far from the Chamizal Memorial and U.S.-Mexico border, whereas previous Texas statues tended to honor conquistadors.

I do believe there is room for a plurality of voices; new monuments and new myths can help to reinterpret the past and to invite participation in a more hopeful future. In a scene from Middlemarch, author George Eliot composes the view from the window of Dorothea’s future house, “happy” on one side, but “melancholy” on the other; she establishes that in “this latter end of autumn”, in the house’s sunless interior “air of autumnal decline” Dorothea’s fiance Casaubon has “no bloom that could be thrown into relief by that background.” Dual images compete for Dorothea’s attention, the happy side including a small park, a fine old oak, a pleasure-ground, and an avenue of limes “melting into a lake in the setting sun.” The landscapes and interiors represent a choice between two futures: from the same single vantage point today, any of us might look ahead in time in multiple directions and project either dismal and sunless or cheerful and pleasant days ahead. We may not have the agency to effect a change in our circumstance when things appear hopeless. Yet our outlook might take on a new shape given the myth in which we find ourselves.

vocational training

Our teaching can take new shape in response to new students. As Philip Davis writes in The Transferred Life of George Eliot (Oxford 2017), George Eliot had begun one novel in 1869 and set it aside, only to begin a “different novel instead” in November 1870, more than a year later.

The story was of an ardent young woman, Dorothea Brooke, a modern St Theresa though ‘foundress of nothing’, seeking, without the structure of a clear faith, a vocation and an epic life in the modern world. … As D H Lawrence said of George Eliot … ‘It was she who started putting all the action inside.’

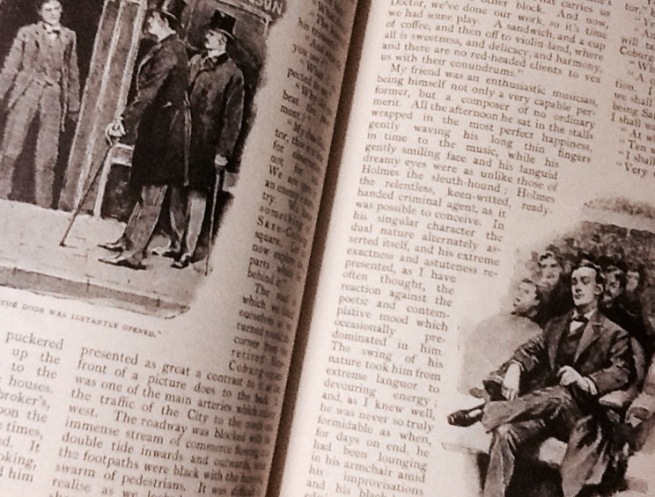

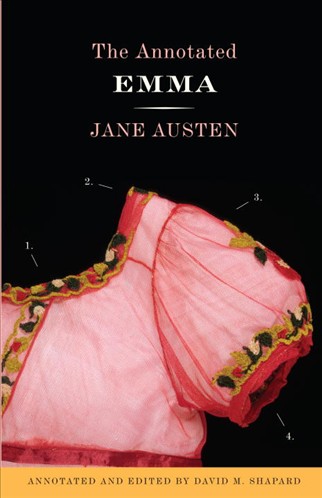

Eliot sets aside one kind of work for another, and her result is Middlemarch, in which she eventually found room to accommodate both stories. And in contrast with film, which by its nature externalizes action, she transfers action to the inside. Her influence is felt in genres as diverse as the mysteries of P.D. James, the hardboileds of Ross Macdonald, and the YA of Sara Zarr.

Marian Evans as the novelist George Eliot is a true teacher, having used the art of poetry to fashion little worlds in which characters investigate vocation, question faith, and imagine better futures. Just imagine if all our classrooms could be little laboratories like hers!

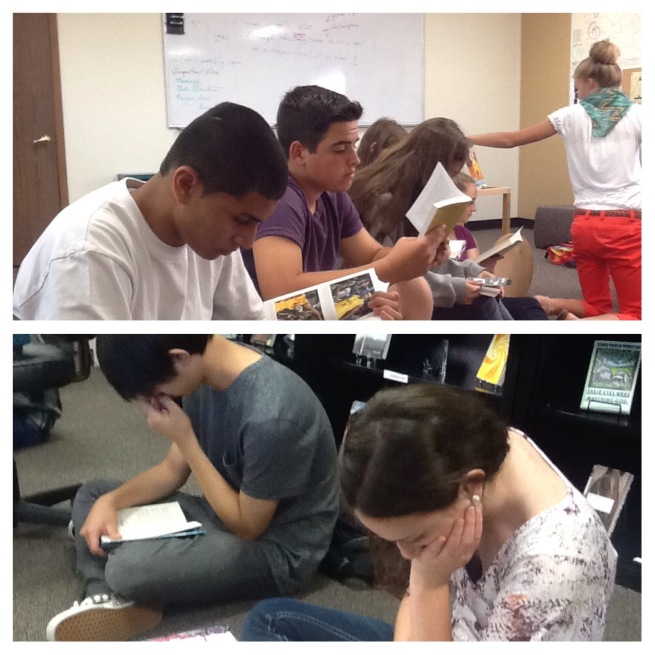

One of the drawbacks to such rooms, worlds, and communities is that it takes a good deal of time to read and probe, through open dialogue – true Socratic dialectic – and reflect on vocation, faith, future, and authority. I feel helpless and disempowered when the school schedule, class size, curriculum, and student interest and inexperience prohibit frequent use of such authentic investigations. Such lack of agency can lead to shame when I seek part-time work for which an education is not required. I have applied for my share of odd jobs in recent month, from library aide to UPS clerk to cafe attendant; and I have done some moonlighting that puts my expertise to work as a copy editor, test-prep tutor, and background actor. At this stage, for me, it is realistic to work part-time jobs, in order to press on toward an ideal class in which students use their voice, participate in community decisions, acquire abiding understanding of ideas and how they work, and have agency.

Such ideals are shaped less, I find, by the myth of teacher-as-hero than by the ability of my students to see themselves as having a role in their own future. Maybe it is time I acknowledge learner-as-hero mythology. [Icarus, Bildungsroman, Fellowship of the Rings, Karate Kid]

changing the narrative

When my students have agency and hope, I am able to step in and guide, support, or nudge them in my role as a learning coach. I can replace outdated or unrealistic myths with models and mentors who show me how to be flexible, patient, and strategic as a teacher. There remains for me a temptation to put off tomorrow, as Scarlet O’Hara does, till “another day”; and to subvert the traditional broken and unjust systems of authority as the anti-hero Dirty Harry does. I have even been attracted to the notion of placing it all on the roulette wheel, cashing out, and leaving the game, like a Casablanca character.

But my calling goes deep, and has a history dating at least back to Socrates, who believed there was justice in showing young people how to question received traditions, systems, and authorities; and there was poetry in the art of speaking properly about humans and divinities. Today social justice is a key term along with agency, and a motivating force in pedagogy which seeks to empower both students and teachers as literate citizens making a difference in society.

Movies and teachers can work to change the narrative stars by which young people sail on their journeys.

Just what America needs in the classroom: one more phallic symbol of authority and force. I remember a much earlier national conversation steered by the Western myth. We considered the “Star Wars defense system” proposed by Hollywood actor-turned-President Ronald Reagan. To most of my friends, such a mistaken idea was a collision between two worlds: one fictional, in which war was glamorized because it symbolized noble human deeds and ideas (Jedi Knights and The Force) pitted against monstrous cruelty and power (Darth Vader and the Death Star); the other nonfiction, in which human beings on either side might bleed and die, and no one could say with certainty which were the monsters and who the humans.

Just what America needs in the classroom: one more phallic symbol of authority and force. I remember a much earlier national conversation steered by the Western myth. We considered the “Star Wars defense system” proposed by Hollywood actor-turned-President Ronald Reagan. To most of my friends, such a mistaken idea was a collision between two worlds: one fictional, in which war was glamorized because it symbolized noble human deeds and ideas (Jedi Knights and The Force) pitted against monstrous cruelty and power (Darth Vader and the Death Star); the other nonfiction, in which human beings on either side might bleed and die, and no one could say with certainty which were the monsters and who the humans.

Enacting Adolescent Literacies across Communities: Latino/a scribes and their rites (2017) offers a hopeful vision where young scribes:

Enacting Adolescent Literacies across Communities: Latino/a scribes and their rites (2017) offers a hopeful vision where young scribes: