Yes, I am obsessed with, and keep returning to Monty Python.

As inspiration, as nostalgia, as poultice; as philosophy.

Thanks in no small part to the gift of the COMPLETE Python collection on DVD, courtesy of best friend and science educator extraordinaire, Susan Berrend. Beneath a shared love of British gardens, humor, and baking shows (and no small affection for Oxford commas and Anglican prayers) resides an even deeper shared commitment to pedagogy, an unwavering interest in discerning student needs and experimenting with new ways to meet those needs.

Which brings me to the force of my allusion to Monty Python and the Holy Grail. King Arthur and his knights are on a quest, but when nearing a treasure horde which may yield the coveted grail, they are frightened by a rampant rabbit.

avoidance strategy

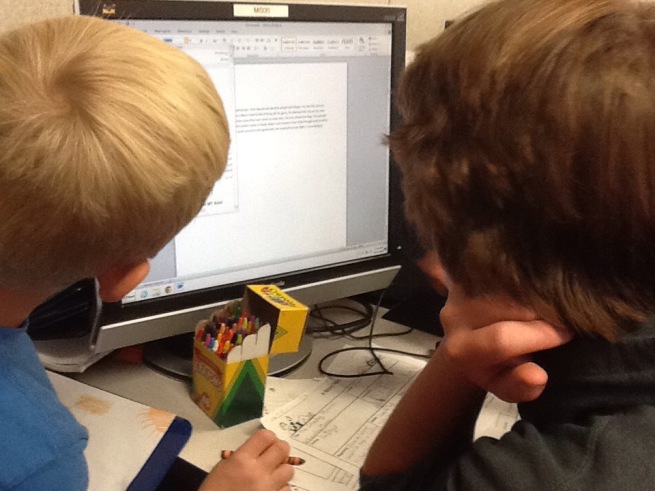

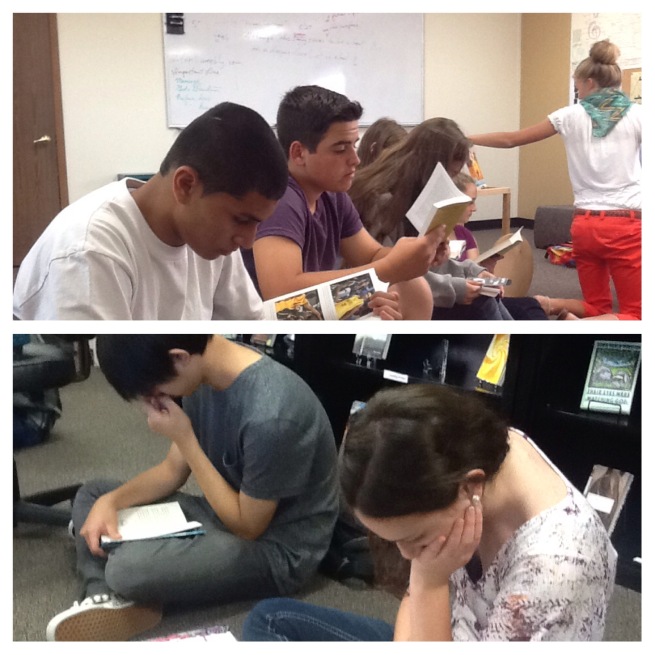

This year I have seen students avoid reading. Some practice what Kelly Gallagher describes in Readicide – where students get assignments done without actually reading. This is ascribed to teacher expectations. One of my students, fascinated by problem-solving, is absolutely convinced that by dedicating time and energy to memorizing punctuation rules and grammar definitions she will inch her way forward and improve her standardized testing score.

Why?

running from or running toward?

Lest I forget that learning is social, and that literacy processes do not occur in a vacuum, these avoidance strategies serve to alert me to the motivating factors in my learners’ worlds.

One learner is driven to complete tasks as quickly as possible in order to move on to the social interactions they look forward to that day. Therefore they will do precisely what the teacher demands, in order to prove to their parent that their calendar is now open to schedule play dates and plan parties. My skill set allows me to integrate even those plans into journaling, research, organizing, and writing-to-learn; I can also involve cooking, makeup, and executive function lessons in authentic and meaningful ways.

For such a student, part of my challenge is to de-school the learner, who will benefit when they see learning as something one does for oneself, as opposed to what one does for others in authority. True, there are wonderful social benefits to the greater community when individuals grow intellectually and acquire wisdom; but one does not learn to love reading just to complete a checklist whose goal is to free one FROM reading.*

race to the finish

Today’s Preakness Stakes reminds me that other learners, like my prescriptive grammarian pupil, run headlong toward a clear goal they have set for themselves, which motivates them. Even if I do not understand the full enticements of these goals, I must acknowledge their power in putting a student in charge of her own learning.

My student can tell me how she learns best, what I should focus on, and how quickly she is improving; she can also relate which fall semester class she wants to qualify for, and how many minutes a day she will dedicate to this finish line. Now, I am no genius, but if you don’t like reading I am not sure why you would want to get into a course that expects you to do a ton of it. The challenge? Actually, I suspect that, like thoroughbreds, the air of competition somehow drives them to top performance.

Yet what role do I play as a democratic instructor who advocates for student voice and shared authority? As a trusted teacher and coach, I can offer advice and exercises that stretch the reader, inviting her take up a text and enjoy it.

I suspect that my I do not fully understand my influence at this time.

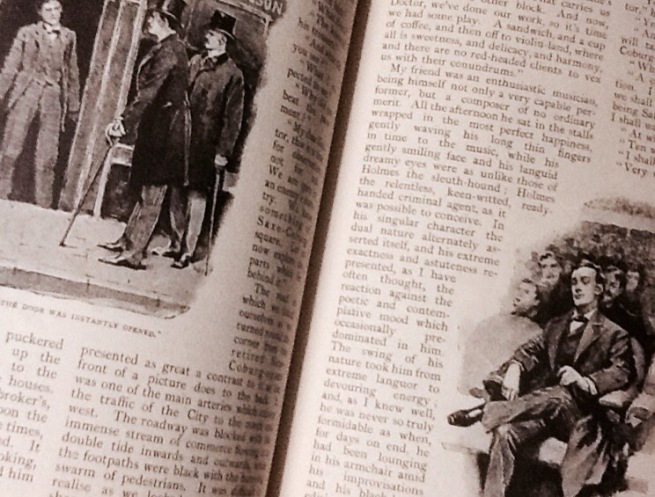

A couple of nights ago a school parent from the past recognized me at a concert, and made a point of telling me “Mr. Hultberg got me to like Shakespeare!” The parent also said that our production of King Lear made Shakespeare clear to them. This was poignant, since the performer on stage was Michael Bigelow, a jazz arranger and saxophonist, who had played Lear in that show, which I stage directed and Berrend tech directed.

I have also received a printed invitation to an upcoming ceremony at my current school, and I R.S.V.P.-ed in person to the preteen who had handed me the slip. She said, “I knew you would dress nice, because you always show … respect for people.”

At this moment I simply want to show my respect for the learning choices my students make, and to honor the freedom I claim to value.

When it is most important in their lives, I have to trust that my role as an engaged reader and lifelong learner will exert its due influence some day.

rabbit rampant

So the next time you are frightened by a rampant rabbit, or notice students running quicky in the opposite direction from which you wish to lead them, P A U S E. Remember that they are on a personal quest of their own, and nothing you can do will alter its course. Confide in your trusted friend as I do in mine; value your relationships with students and colleagues, knowing that others will be inspired by your commitment. Trust that what is most important to you – a garden, music – will not fail to exert its due influence in its time.

*Checklists: As I write this post, many of my students are actively engaged in reading ten books this summer in order to win free passes to the state fair!

Image at http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_7FAsUT6FePU/SWOhlsoMZgI/AAAAAAAAAdA/1Emq5jvchOc/s1600-h/Holy-Grail-Killer-Rabbit-Posters.jpg cited in Moviedeaths.blogspot.com

Degas painting public domain

Photo by GH pradlfan 5/17/2018

instruction and a catalyst for both more

instruction and a catalyst for both more