I was startled when I discovered that architecture and fragrance could be the subjects of essays. My discovery opened up new realms of nonfiction for me as I became aware that good writers can reveal hidden processes, invisible forces and ideas, and interesting personalities. My New Year’s resolution: to ensure that my students have opportunities to discover for themselves the power of essays.

I suspect now that I had always assumed commercial, aesthetic, and functional uses alone dictated the design and execution of buildings and colognes, if I thought about it at all.

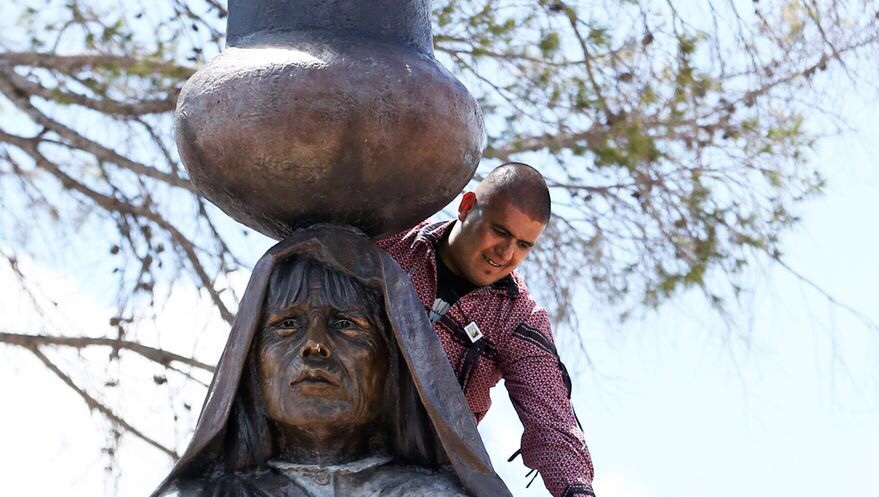

It should have been clear to me at 12 years old that the sculpture pictured above could not be explained by ordinary “sense” – it did not make economic, artistic, nor practical sense to have this concrete fountain near the San Francisco waterfront.

A few years later I walked past another architectural marvel, one denigrated by my professors at S.F. State.

In the 1980s, I would read Allan Temko of the SF Chronicle reviewing new buildings, such as art museums. Temko, 1988 finalist for a Pulitzer, engaged me with his reviews. At the time, in college, I read film and theater criticism religously; I admired that a writer could treat a building as if it were literature, as though its existence incarnated an idea worth listening to. https://atlanticyardsreport.blogspot.com/2006/05/raising-hell-allan-temko-and-foxes.html

The New Yorker once ran a piece by Chandler Burr profiling perfumer Jean-Claude Ellena. Burr’s 2005 article refers to essais, story, poetry, art, and signature: building a montage of language that persuades me that builders of a fragrance are artists seeking expression of an idea.

So, having discovered the startling power of essays, I was startled in an opposite way last week as I began to hear a concern from my middle school students: “Someone told me there is an essay due!” In fact, I had avoided using the term “essay” for precisely this reason; it awakens a “school” mindset and deadens the “learning” mind and lively writing that accompanies interest and inquiry. I had called the assignment “letter to a reader”, and had buried Nancie Atwell’s (In the Middle) term “letter-essay” deep in the details of the assignment. Not deep enough.

Stand-ins

Of course, the sculpting of concrete and the layering of scents are only stand-ins for activity of all kinds, and for the keen observation and reflection that leads to compelling writing projects. A paper written to fulfill a teacher’s assignment may not even properly deserve the name essay. What I began seeing in the final days of the Fall term were less like dreary essays or letters, and more like short notes with a summary appended. Here is what happened.

The week before the holiday break I received the dull writing I had steered away from all term. Although the letters I received in early December were glorious, were actual letters written to me as a person–about a free reading book, its world, and the mind of my young reader exploring that world, inviting me into it–despite the glorious early letters, “the ravages” of the final week, as O Henry might have put it, cannot be undone. One writer offered a single paragraph intro and conclusion, engorged with 5 pages of summary. Another shared a two-page cutting from their book, and a paragraph tagged on at the end explaining their choice (but not?).

Hope ahead

But I proceed with excitement toward an upcoming series of classroom writing events. Inspired by Sarah M. Zerwin’s Point-less and Liz Prather’s Project-Based Writing; Tom Newkirk’s Unbound and Kwame Alexander’s Write Like This; I am feeling confident and hopeful that my learners will progress toward “secure” and “expanding” in their control over writing processes, those terms the upper half descriptors I use in our recent move away from traditional grades and toward a learning focus.

One thing these writing-focused books for teachers share is a passionate affection for offering writers STUDIO TIME. When students are given the opportunity to write, rework, receive feedback, self-evaluate, and publish all kinds of writing–poems, fiction, or nonfiction genres–they practice important decision-making strategies that are transferable to many other goals. As far as my resolution goes, these opportunities become essential for the discoveries that are about to happen.

Their writing is about to leap off the page. I am reading a fair share of recent nonfiction myself, such as Homer: The Very Idea (James I. Porter) or The Lost Pianos of Siberia (Sophy Roberts) and recent essays by Robert Clark on Sylvia Plath’s house, Sara Zarr on Nomadland, or Jonathan Lethem on J.G. Ballard’s science fiction short stories.

In most cases, the essayists offer an anchor by writing about people who have gone through turbulent times, and the authors consider their and our response to what Malcolm Andrews this month called “the growing complexities of life.” Addressing the Dickens Fellowhip, he invited participants to critically read paintings that hearken back to an idealized view of the countryside and its landscape. Whether “reading” modern architecture, Victorian parks, profiles, or van life, good essayists enlist readers in a journey. They help us see what is under the surface, and offer us fresh ways of seeing.

fresh sight

…For to hear or read a verse of Homer was to do more than simply listen to a song. It was to be put in touch with a reality that was no longer accessible except through the medium of the poems: it was to see directly through the poet’s eyes.”

James I. Porter (p. 26, University of Chicago Press 2021)

Whatever I do as a teacher, I hope that I promote the sort of authentic writing that can engage with a changing world, that can open a window to the past, offer a glimpse of the future, and speak to the present.

It is not too much to expect even that my students will come to their own experiences of art, nature walks, urban trails and open spaces expecting journey and story. Even further, I resolve to provide them with studio time: opportunities to write about their explorations and discoveries in order to reflect on those events — their meaning and idea. If cologne can tell a story, if journalism has a point of view, and if Dickens scholar Andrews is correct, and “sweet view[s]” in the England of Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, and George Eliot imply perspectives or people whose assumptions and stories are worth examining, then the daily life experiences and interests of my own students contain similarly valuable stories.

And beyond writing itself, I want for young people to view the world as a place they can inhabit, alter, address, and create in. I hope they feel a freedom in believing that a building they might design can express ideas, and that a fragrance, a line of clothing, or a food menu they create communicates a point of view, as is often emphasized by two of my favorite encouragers/educators [I kids you not] Tim Gunn and Gordon Ramsay. When I take time to sit, write, walk, and to really reflect on their and my learning cycles, our parallel paths find a meeting point. Is that a vanishing point? I am curious what disappears when I become co-learner. I think I will have greater empathy with students, more patience with their individual processes. Can I wait till the end of the school year to find out what discoveries they have made? Time will tell.